What does “Kosher” mean?

The term “Kosher” refers to eating limitations imposed upon religiously observant Jews.

The three basic laws of Kosher are:

01

Certain animal ingredients are not to be consumed, under any circumstances.

main groups of forbidden ingredients are those taken from mammals that do not have split hooves or do not chew their cud, any type of shellfish, fish that do not have scales, or any other animal that is not a mammal, poultry, or fish. Over the generations, pork became a symbol of forbidden foods, since Jews in certain exiles were made to eat this meat as a symbol of renouncing their religion. A potentially Kosher animal will become Kosher for consumption only if it had been slaughtered in a traditional manner by a certified slaughterer (“shochet”).

02

Animal and dairy products are not to be consumed simultaneously:

dairy meals and meat meals should be separated by several hours, and each type of food should be cooked and served in separate utensils. Obviously, any mixed meat-dairy dish, such as a cheeseburger, is strictly forbidden. A third food category, “Pareve” or “Parve”, refers to any ingredient that is not meat, poultry, or dairy: fish, eggs, plants. These products can be consumed simultaneously with either meat or dairy dishes.

03

A kitchen will not be considered Kosher unless the household, manufacturing plant, POS or restaurant observe the rules of Sabbath and High Holidays.

These rules forbid, among others, any lighting of fire or electricity, and any actions that might be considered as work (unless needed for the physical well being of people). In practice, this means that all food preparations must take place before the Sabbath begins (sunset on Friday evening). In orthodox households, a host of modern aids help keep these rules: a low-heat electric plate is turned on before the Sabbath begins, and continuously heats the foods; a “Sabbath clock” is preset to turn lights on and off, etc.

For restaurants, this issue is even more complicated, since any type of work or exchange of money is forbidden. In general, restaurants that need to be strictly Kosher are closed on weekends.

An interesting case is the Israeli hotels, which are required to serve food at all times, but need to be strictly Kosher. Their weekend staff has a majority of non-Jews, the meals served are pre-prepared, and the charges are usually added to the room bill and not paid during the Sabbath.

What does “Halal” mean?

The term “Halal” refers to eating limitations imposed upon observant Muslim. The basic laws of Halal are:

- Certain ingredients are not to be consumed, under any circumstances. The main groups of forbidden ingredients are pork and alcohol.

- Animal products should originate in an establishment that uses traditional slaughtering.

Holidays

During certain holidays there are additional food restriction or traditions, and these should be taken into consideration when planning fieldwork.

- Jewish Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) – a day of complete fasting

- Muslim Ramadan – a whole lunar month in which food and beverage intake is only permitted after sundown and before sunrise

- Jewish Passover – any leavened product (such as bread) is not permitted

- Several other holidays, of all religions, have different traditions concerning foods. For example, the Jewish Shavu’oth is characterized with dairy-based dishes.

Both Jewish and Muslim calendars are lunar-based, which means that the dates of holidays change from one year to another. The Jewish calendar “corrects” itself every few years with an additional, 13th, month, so shifts in dates are not extreme. However, the Muslim calendar does not, and therefore Muslim holidays, Ramadan included, can occur in all seasons.

Recommendations

Please consult with us before planning a study about food consumption; inappropriate fieldwork dates may result in skewed results, and certain questions should be adjusted for the culture.

Politics

The Jewish Kosher certification industry is very strong and lucrative. By law, the Chief Rabbinate Office, a government organization, is the only body allowed to certify food items. However, along the years some ultra-orthodox organizations added their own certification, claiming that the government one is not good enough. Several food companies, in order to be present in all segments, pay for certification of several organizations.

Since certification is quite expensive, this system adds to the cost of all food items. In an attempt to lower this expense, Minister of Religions Matan Kahana proposed abolishing the monopoly of the Chief Rabbinate in the field of Kosher, and to make it a regulator of external bodies that would offer these services.

The implications of the new law are expected to be a reduction in household spending as a result of the decline in the cost of supervision, but the responses to it are mixed: several strong groups that may lose power if the change takes place have launched campaigns among observant Jews to oppose this law.

The following study aimed to measure the proportion of Israeli Jews that will be affected by the law, and their reactions to it.

Attitudes towards the proposed Kosher Law - Introduction

In this study, the attitude towards the law was examined among various segments of Jewish society in Israel. The study was carried out shortly after the discussion began, and therefore the knowledge of the respondents regarding the percentage of savings in household expenditure was extremely limited, and this must be taken into consideration.

As part of the study, 1,166 Hebrew-speaking Jews aged 18 and over were interviewed, in a random representative sample of the Jewish population in Israel. A sample of this magnitude allows for a high level of accuracy – the confidence interval, at p=0.95, is ±2.9%.

The study was conducted face-to-face in the respondents’ homes, spread over 146 PSUs, stratified by district, size of locality and socioeconomic level of the statistical area. This methodology is extremely rare today, since its cost – in time and money – is high. At the same time, it is the only methodology that allows accurate and representative sampling, and enables hearing the voice of segments that are often absent from the group of survey respondents.

Attitudes towards the proposed Kosher Law - Summary

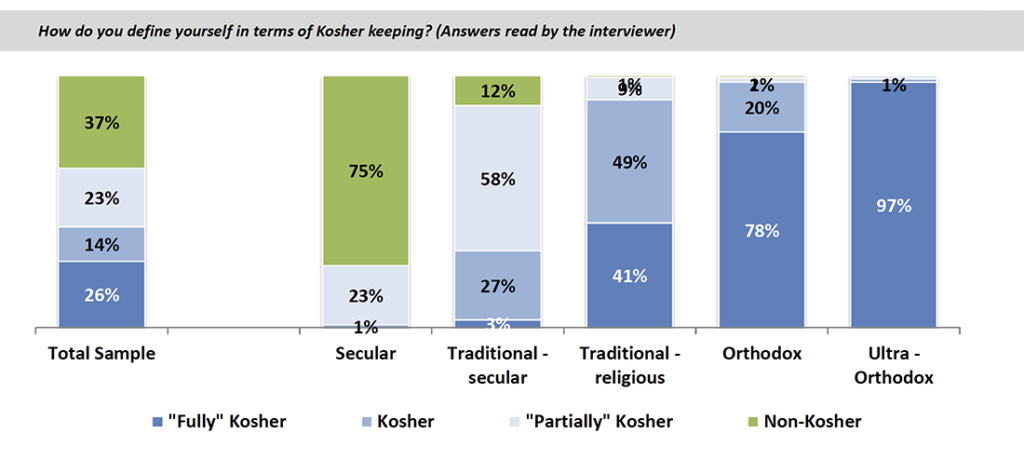

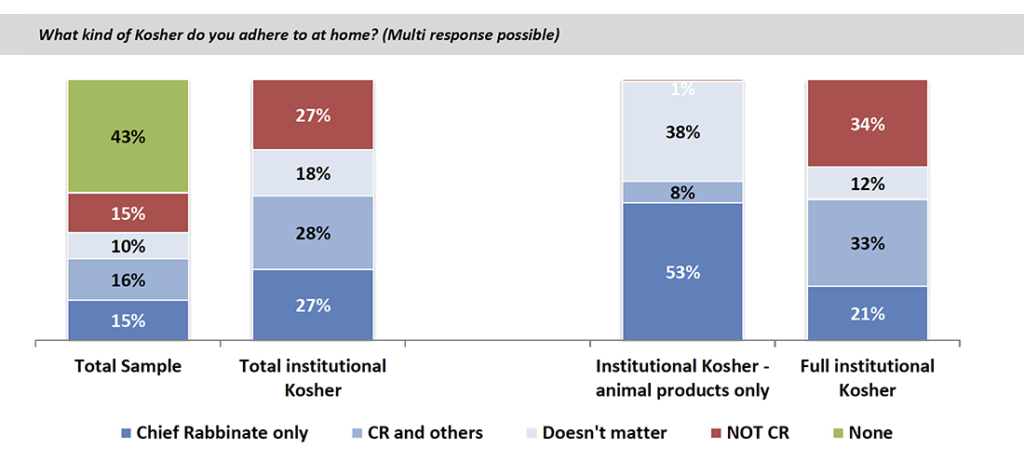

37% do not keep Kosher at all, and 26% define themselves as “full” Kosher keepers. In between are another 37% who define themselves as “partial” Kosher keepers. 57% are consumers of institutional Kosher certification, to any extent. This figure increases sharply with the level of religiosity.

Among non-ultra-orthodox sectors, and especially traditional ones, there is some flexibility regarding food certification, e.g., willingness to eat in restaurants that are not “Kosher” by certification or even in practice, and “partial” adherence to Kosher rules (usually those related to animal products).

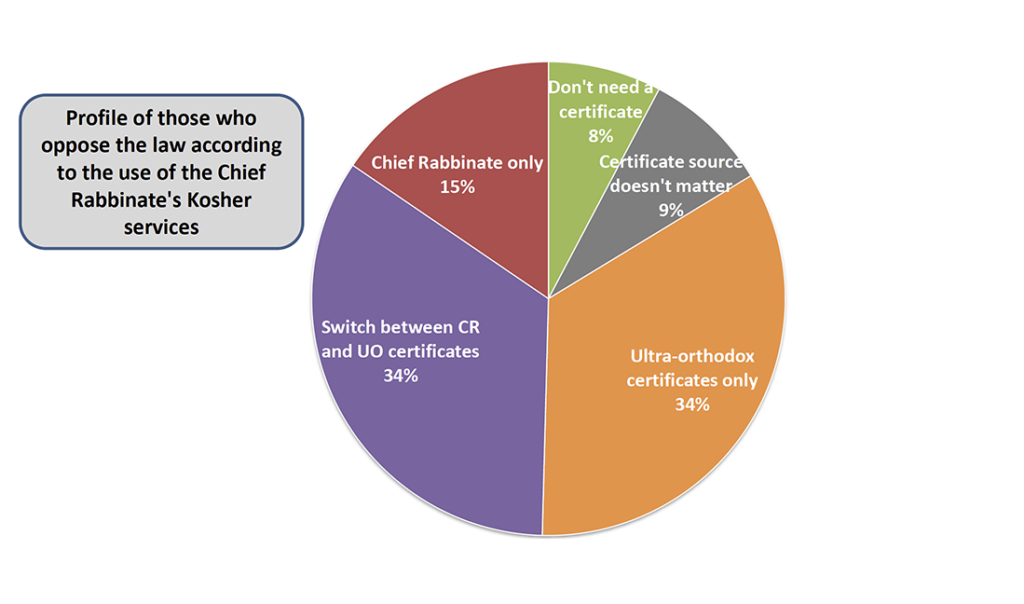

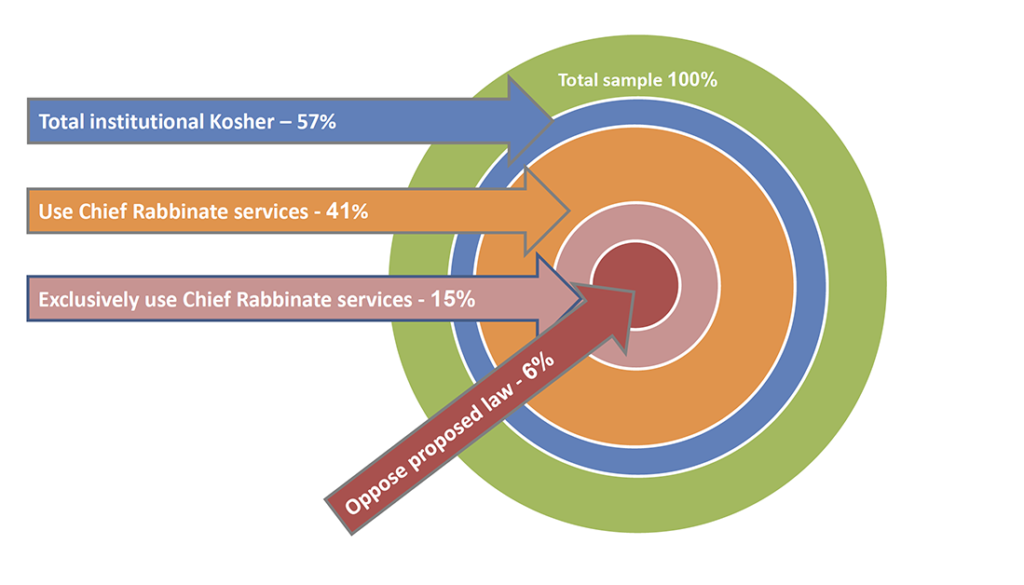

Half of the total sample support the new law, compared to about 40% who oppose it. The most vulnerable segment, if the new law is applied, are those that currently use only the Kosher certification of the Chief Rabbinate. This group accounts for 15% of the total sample, and the proportion of opponents belonging to this group constitutes 6% of the sample.

The bulk of the opposition to the proposed law comes from groups that will not be harmed, or only slightly harmed, by the law:

- About a third of opponents approve only ultra-Orthodox Kosher certificates, and do not use the Kosher certification of the Chief Rabbinate

- About 10% do not adhere to Kosher or Kosher certification at all

- About 10% stated that they accept all certifications, without any preference, and about a third varied between Kosher certificates of the Rabbinate and ultra-orthodox organizations: these respondents will not be harmed, since they will be able to continue to use the other certifications available.

- Only 15% of those who oppose the law come from the exclusive user segment of the Chief Rabbinate.

Attitudes towards the proposed Kosher Law - Results

As expected, the proportion of those who define themselves as Kosher keepers sharply increases with religiosity.

Among the group of traditionalists, those who are prone to secularism tend to use the term “partial keeper”, while those who lean toward religiousness tend to use the terms “Kosher keeper” and “full Kosher keeper”.

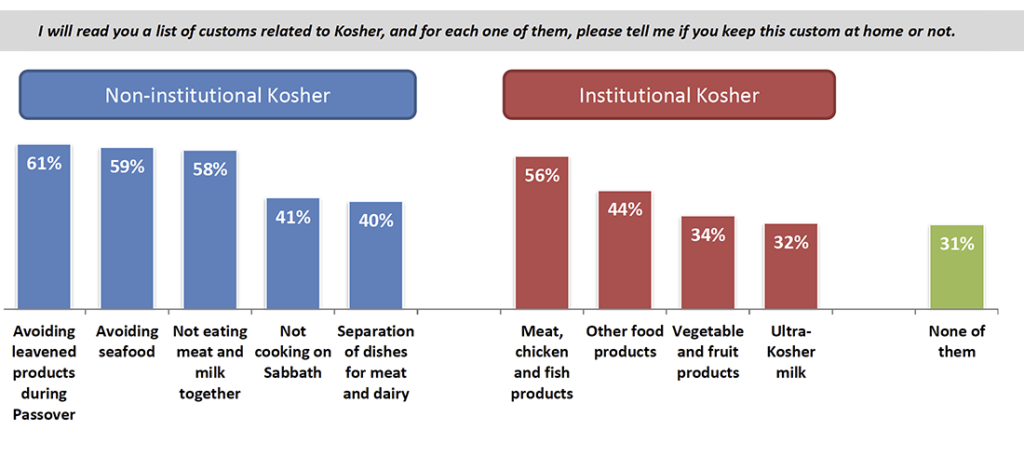

In the context of this study’s subject matter, it is important to measure two content worlds of Kosher keeping - the one that requires a supervisory body ("institutional Kosher") versus the one conducted within the household ("noninstitutional Kosher").

Within a household that maintains some level of Kosher, the common actions are the avoidance of certain foods. In the institutional Kosher category, the dominant category is animal products.

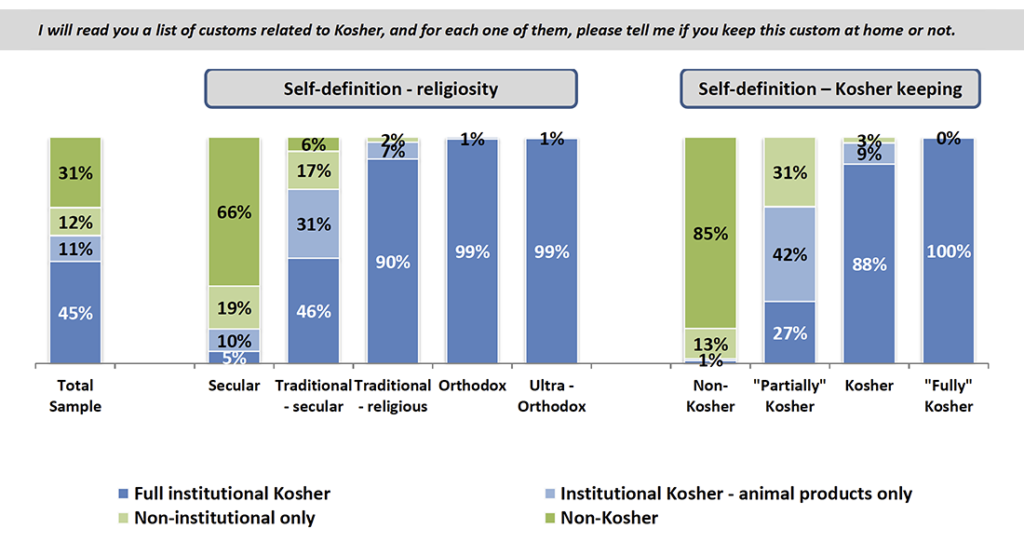

57% are consumers of institutional Kosher certification, to any extent. This figure increases sharply with the level of religiosity.

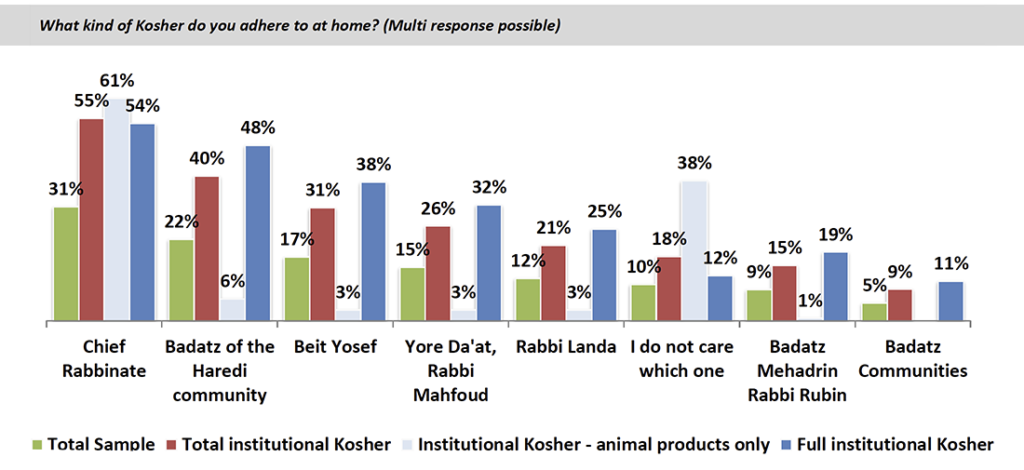

More than half of institutional kashrut consumers (31% of all Jews) are consumers of Kosher supervision of the Chief Rabbinate, exclusively or in combination with other kashrut bodies.

Nearly 20% of institutional Kosher consumers are indifferent to the body that grants the certificate. In this group there is over-representation of respondents who require a Kosher certificate only for meat, poultry and fish products.

On average, each consumer indicated 2.4 Kosher certificates entities approved in the household.

About three-quarters of consumers of Kosher certificates (about 40% of the total sample) use the supervision of the Chief Rabbinate, although only about a quarter (15% of the total sample) use this supervision exclusively.

The exclusive reliance on the supervision of the Chief Rabbinate is especially noticeable among respondents who need a Kosher certificate for meat products only.

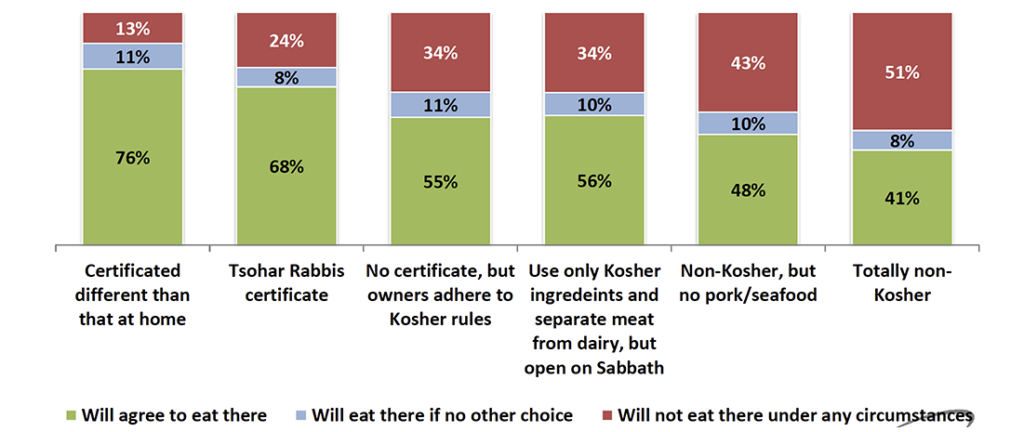

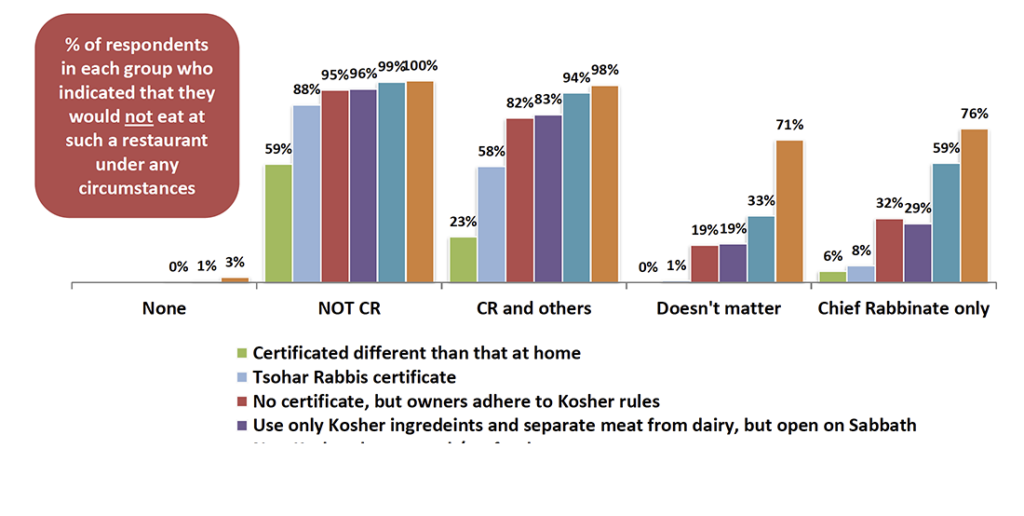

Because the Chief Rabbinate's services are also provided outside the home, flexibility was examined in various scenarios in which the respondent was required to decide whether to eat at a restaurant that offers a vegan option but does not fully meet the exact Kosher definitions at home. From the results among all respondents, including those who do not keep Kosher, it can be seen that the flexibility outside is indeed higher than that practiced at home.

Please imagine a situation in which you are far from home and need to eat at a restaurant. For each of the restaurants I will describe to you, please tell me If you would agree to eat there, you would agree to eat there only if there were no other choice, or you would not agree to eat there under any circumstances. For the purpose of the question, Please assume that all restaurants have a variety of vegan dishes that do not contain meat or dairy products.

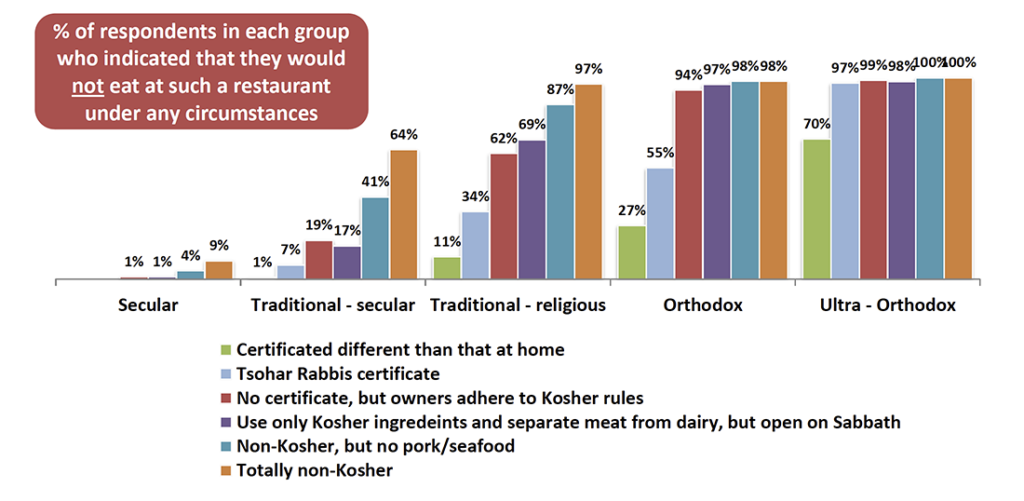

As the level of religiosity increases, the willingness to compromise outside the home decreases.

Please imagine a situation in which you are far from home and need to eat at a restaurant. For each of the restaurants I will describe to you, please tell me If you would agree to eat there, you would agree to eat there only if there were no other choice, or you would not agree to eat there under any circumstances. For the purpose of the question, Please assume that all restaurants have a variety of vegan dishes that do not contain meat or dairy products.

Among Chief Rabbinate consumers, especially those who require this Kosher only, or those for whom the source of Kosher is not important, the willingness to compromise outside the home is greater.

Please imagine a situation in which you are far from home and need to eat at a restaurant. For each of the restaurants I will describe to you, please tell me If you would agree to eat there, you would agree to eat there only if there were no other choice, or you would not agree to eat there under any circumstances. For the purpose of the question, Please assume that all restaurants have a variety of vegan dishes that do not contain meat or dairy products.

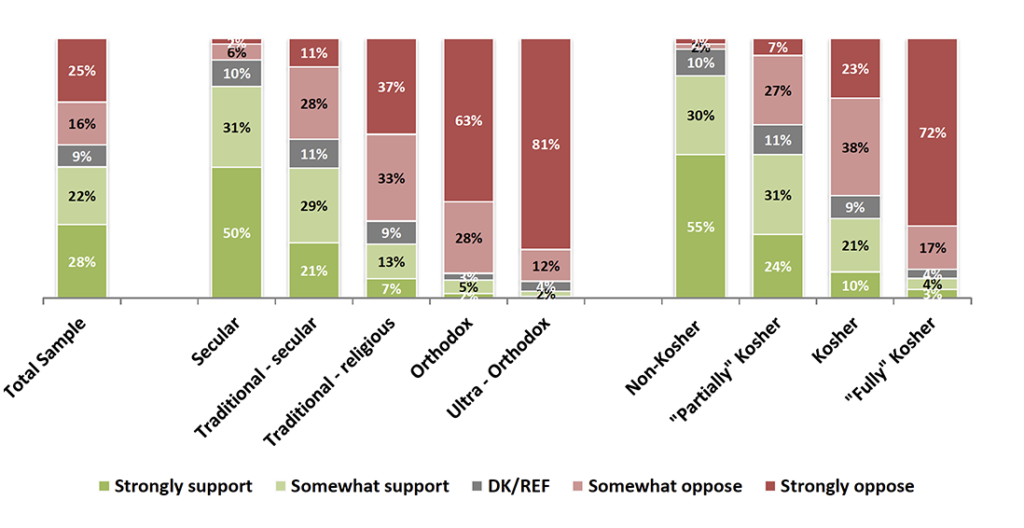

Opposition to the proposed law increases with self-definitions of religiosity and the degree to which Kosher is maintained.

The Chief Rabbinate, currently, is the only body authorized to provide Kosher certificates in the country. Recently, a proposal was made in the government to allow various organizations to grant Kosher certificates, with the Chief Rabbinate supervising these organizations, but not carrying out the actual work. What is your position on this change?

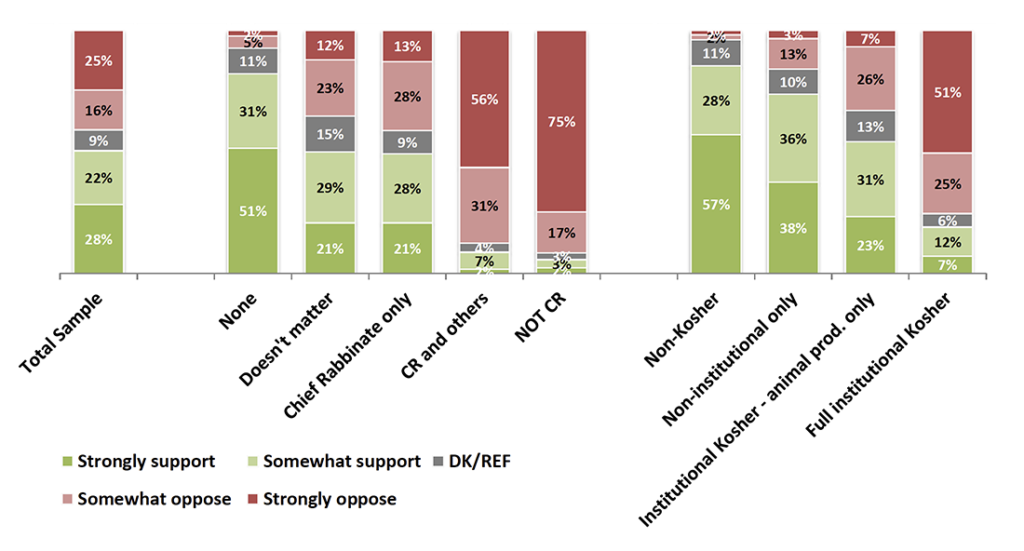

Half of the sample support the law, compared to about 40% who oppose it. An almost identical distribution was observed among customers of the Chief Rabbinate who do not use other Kosher services. Resistance is particularly high among those who do not use the Chief Rabbinate's Kosher services.

The Chief Rabbinate, currently, is the only body authorized to provide Kosher certificates in the country. Recently, a proposal was made in the government to allow various organizations to grant Kosher certificates, with the Chief Rabbinate supervising these organizations, but not carrying out the actual work. What is your position on this change?

6% of the total sample currently consume the Kosher services of the Chief Rabbinate exclusively, and oppose the proposed law. This is the segment that will be harmed by the implementation of the new law.

Of those who oppose the proposed law, 42% do not use the Chief Rabbinate's training services at all. Another 43% are those who currently shift between different Kosher services, so the magnitude of harm to them is low. Only 15% of all those who oppose the law are respondents for whom the Chief Rabbinate is the exclusive source of a Kosher certificate.